Chapter 1 Catalyzing the Generation of Knowledge 第1章 促进知识的产生

1.1. THE LEARNING PROCESS 1.1 学习过程

Knowledge is power. It is the key to innovation and profit. But the getting of new knowledge can be complex, time consuming, and costly. To be successful in such an enterprise, you must leam about learning. Such a concept is not esoteric. It is the key to idea generation, to process improvement, to the development of new and robust products and processes. By using this book you can greatly simplify and accelerate the generation, testing, and development of new ideas. You will find that statistical methods and particularly experimental design catalyze scientific method and greatly increase its efficiency.

知识就是力量。关键是如何创新和利用知识,但是知识的获得可能是复杂的,要花费时间和付出代价。为了事业上获得成功,你必须学会如何学习。学习这一概念并不深奥,要紧的是如何使好的思想得以产生、达到一个过程的改进、一个新的稳健产品或工艺得到开发,等等.通过使用这本书,你可以发现如何大大简化和加速知识的产生、检验以及新思想的发展过程.同时你也会发现统计方法(特别是试验设计)是催化新知识产生的科学方法并且可以大大提高效率。[2]

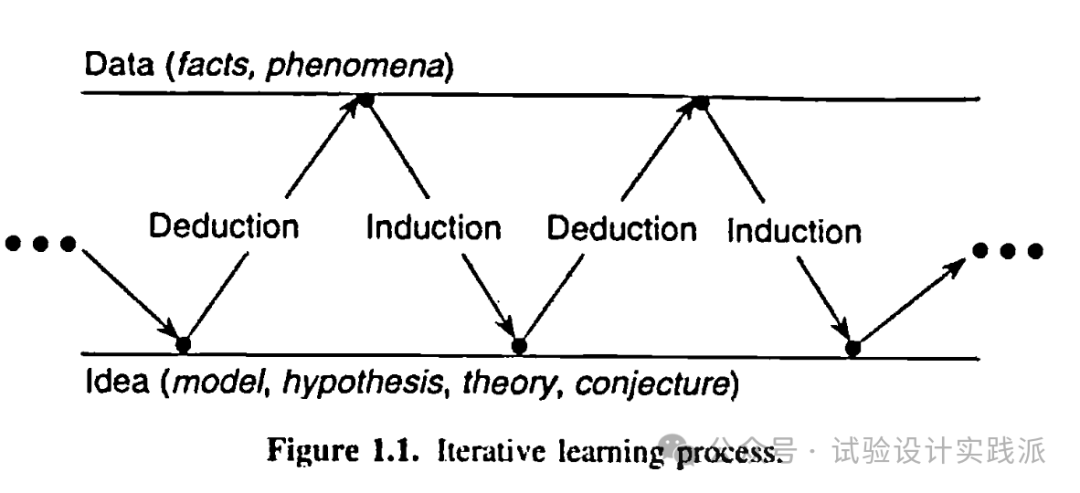

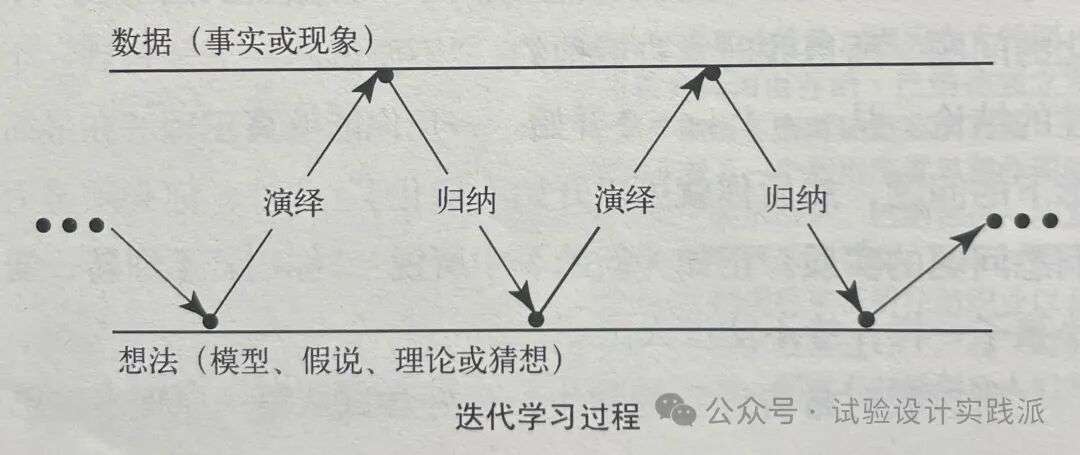

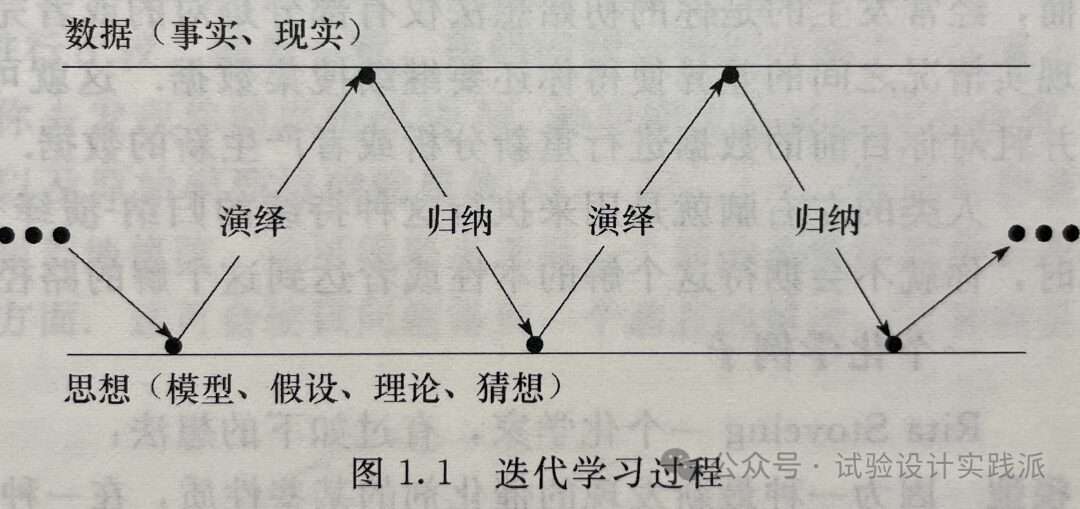

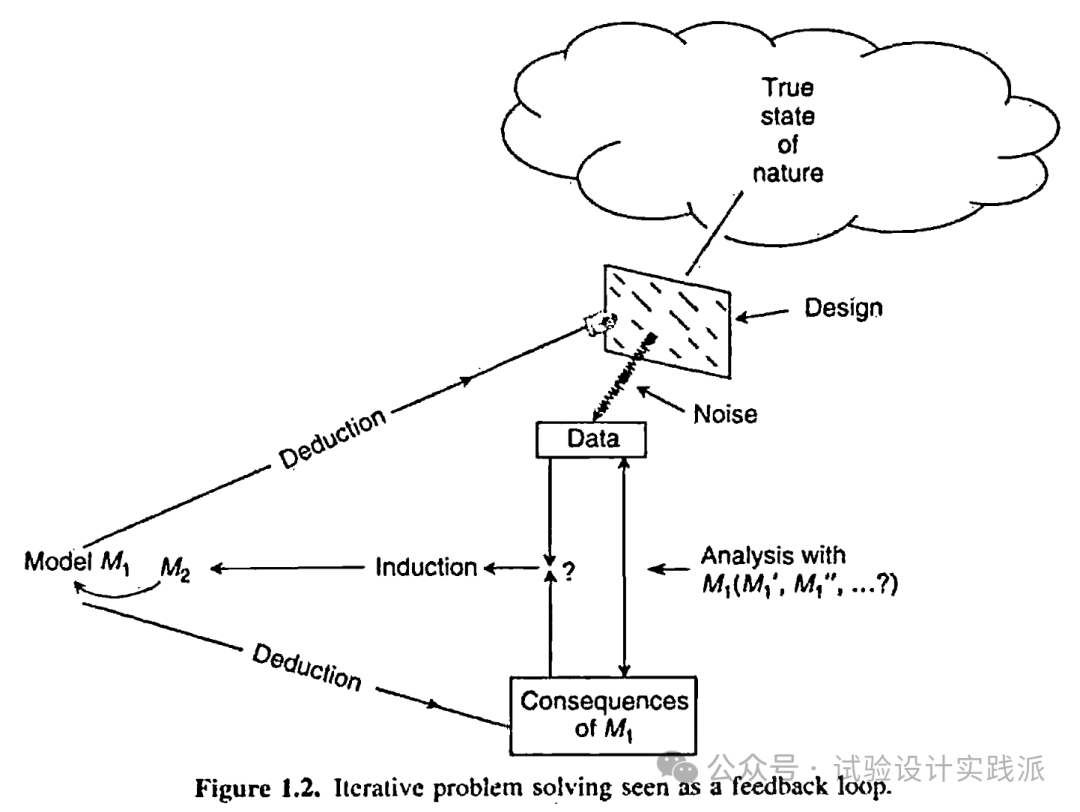

Learning is advanced by the iteration illustrated in Figure 1.1. An initial idea (or model or hypothesis or theory or conjecture) leads by a process of deduction to certain necessary consequences that may be compared with data. When consequences and data fail to agree, the discrepancy can lead, by a process called induction, to modification of the model. A second cycle in the iteration may thus be initiated. The consequences of the modified model are worked out and again compared with data (old or newly acquired), which in turn can lead to further modification and gain of knowledge. The data acquiring process may be scientific experimentation, but it could be a walk to the library or a browse on the Internet. [3]

一个初始想法(模型、假说、理论或猜想)通过一个演绎过程,得到特定必然的结论,后者可与数据相比较。当结论与数据不一致时,这种偏差可通过一个归纳过程,引出对于模型的修订。由此可以开始第二轮迭代。演绎得到修订后的模型的结论,然后再次将之与(旧的或者新获取的)数据相比较,继而反过来继续修订模型或者得到新知识。这里的数据获取过程可能是科学实验,也可能是去一趟图书馆或者上网浏览。[1]

学习是通过如图1.1所描述的反复过程而进行的。开始由一个可以用数据来比较的某些必要结果的演绎(deduction)过程引导出来一个初始的思想(模型、假设、理论或者猜想)。当结果和数据不一致时,通过一个叫做归纳(induction)的过程,这种差异可以导致对模型的修正。于是开始在迭代中的第二个循环,计算出所修正的模型的结果并且再一次和(旧的或新获得的)数据进行比较,依此下去,可能得到进一步的修改并获得知识。获得过程的数据可以是通过科学实验,但也可以是通过到图书馆查询或到互联网上浏览。[2]

Inductive-Deductive Learning: An Everyday Experience 归纳-演绎学习:日常体验

The iterative inductive-deductive process, which is geared to the structure of the human brain and has been known since the time of Aristotle, is part of one’s everyday experience. For example, a chemical engineer Peter Minerex parks his car every morning in an allocated parking space. One afternoon after leaving work he is led to follow the following deductive-inductive learning sequence:[3]

这种迭代的演绎-归纳过程与人脑结构相契合,早在亚里士多德的时代就为人所知,现在已经成为人们日常经验的一部分。比如,我们的化学工程师彼得每天早上都会把车停在分配给他的固定车位上。一天下午下班时,他就进行了如下一个演绎-归纳学习序列:[1]

反复的归纳-演绎过程是人们日常体验的重要部分,它适合于人脑组织结构,并且自古希腊大哲学家亚里士多德(Aristotle)时代就已广为人知了。例如,一个化学工程师Peter Minerex每天早晨把他的车停在分配的停车位置。下班后的一天下午,他遵循如下的归纳-演绎学习顺序:[2]

|

Model: Today is like every day. Deduction: My car will be in its parking place. Data: It isn’t. Induction: Someone must have taken it. |

模型:今天如同以往。 演绎:我的车会在车位上。 数据:车不在车位上。 归纳:必定有人把它偷走了。[1] |

模型:今天和往常每天一样. 演绎:我的车会在它的停放位置. 数据:它不在那个地方. 归纳:一定有人把它开走了.[2] |

|

Model: My car has been stolen. Deduction: My car will not be in the parking lot Data: No. It’s over there! Induction: Someone took it and brought it back. |

模型:我的车被偷了。 演绎:我的车不会在车位上。 数据:不对,车在那一边! 归纳:有人偷走它,然后又把它送回来了。 |

模型:我的车被人偷了. 演绎:我的车会不在那个停车场地. 数据:不,哦,它就在那边! 归纳:有人把它开走了但又放回来了. |

|

Model: A thief took it and brought it back. Deduction: My car will have been broken into. Data: It’s unharmed and unlocked. Induction: Someone who had a key took it. |

模型:偷车贼偷走我的车,然后又把它送回来了。 演绎:我的车会有被撬开的痕迹。 数据:车完好无损,是被正常打开的。 归纳:有人拿车钥匙开走了它。 |

模型:一个小偷开走了但又放回来了. 演绎:我的车可能被损坏了. 数据:它没有被损坏而且没有锁. 归纳:是有人有钥匙开走车的. |

|

Model: My wife used my car. Deduction: She probably left a note. Data: Yes. Here it is. |

模型:我的妻子用了我的车。 演绎:她很有可能会留下纸条。 数据:确实,我发现纸条了。 |

模型:我太太用过我的车. 演绎:她可能在车里留了纸条. 数据:是的,你看,纸条就在这儿. |

Suppose you want to solve a particular problem and initial speculation produces some relevant idea. You will then seek data to further support or refute this theory. This could consist of some of the following: a search of your files and of the Web, a walk to the library, a brainstorming meeting with co-workers and executives, passive observation of a process, or active experimentation. In any case, the facts and data gathered sometimes confirm your conjecture, in which case you may have solved your problem. Often, however, it appears that your initial idea is only partly right or perhaps totally wrong. In the latter two cases, the difference between deduction and actuality causes you to keep digging. This can point to a modified or totally different idea and to the reanalysis of your present data or to the generation of new data.

假设你想解决某个具体问题,而基于初始的猜想,你得到了某个相关的想法。然后你会收集数据,以支持或反驳这个理论。这时你可以做如下一些事情:进行一次文件或网络检索,去一趟图书馆,与你的同事或老板进行一场头脑风暴,对一个过程进行被动观察,或者进行主动实验。不论哪种方式,你收集到的事实和数据有时会支持你的猜想,这时你就解决了这个问题。但更多时候,你的初始想法看上去只是部分正确或者或许是完全错误的。对于后两种情况,演绎结果与事实之间的偏差会让你继续挖掘探索。这可能会指向一个经修订的或者全新的想法,以及重新分析你的现有数据或者重新收集新的数据。[1]

假设要解决一个特定问题并且初始的思索提出某些相关的想法或理论。然后就会寻找数据来进一步支持或者否定这一理论。这可能由以下某些方面组成:你的领域和互联网的搜索、步行到图书馆查询、与合作者和执行者的讨论会,对过程的被动观测或者主动试验,在任何情况下,事实和收集到的数据有时会进一步证实你的猜想,此时你可能已经解决了你的问题。然而,经常发生的是你的初始想法仅有部分是对的或者完全是错的。在这后两种情况下,演绎和现实情况之间的差异使得你还要继续搜集数据。这就可能导致一种修正或者完全不同的想法,并且对你目前的数据进行重新分析或者产生新的数据。[2]

Humans have a two-sided brain specifically designed to carry out such continuing deductive-inductive conversations. While this iterative process can lead to a solution of a problem, you should not expect the nature of the solution, or the route by which it is reached, to be unique.

人脑的结构就被设计成能够进行这样一种持续不断的演绎-归纳对话。尽管这种迭代过程最终能够解决问题,但你不应该预期解答本身或者求解过程的性质是唯一的。[1]

人类的左右脑就是用来执行这种持续的归纳-演绎交流的。当这种反复过程能够解决问题时,你就不会期待这个解的本性或者达到这个解的路径是唯一的。[2]

A Chemical Example一个化学例子

Rita Stoveing, a chemist, had the following idea:

Rita Stoveing一个化学家,有过如下的想法:[2]

|

|

Because of certain properties of a newly discovered catalyst, its presence in a particular reaction mixture would probably cause chemical A to combine with chemical B to form, in high yield, a valuable product C. 因为一种最新发现的催化剂的某些性质,在一种特定反应混合物中它的存在可能会造成化学药品A跟化学药品B以高产量形成一种有价值的产品。[2] |

|

|

Rita has a tentative hypothesis and deduces its consequences but has no data to verify or deny its truth. So far as she can tell from conversations with colleagues, careful examination of the literature, and further searches on the computer, no one has ever performed the operation in question. She therefore decides she should run some appropriate experiments. Using her knowledge of chemistry, she makes an experimental run at carefully selected reaction conditions. In particular, she guesses that a temperature of 600°C would be worth trying. 丽塔有一个试探性的假设并且推断出它的结果,但是没有数据来验证或者否定它的真实性。根据和同事们交谈、小心地查阅文献以及在计算机上的更进一步地搜索,她确认还未曾有人实施操作来完成这一课题。因此,她决定进行一些适当的试验。应用她的化学知识,她要在一个细心选择的条件上做一个试验。特别地,她猜想温度600℃应该值得一试。 |

|

Data 数据 |

The result of the first experiment is disappointing. The desired product C is a colorless, odorless liquid, but what is obtained is a black tarry product containing less than 1% of the desired substance C. 第一个试验的结果令人失望。所要求的产品C是一种无色、无味的液体,而目前所得到的是一种黑色焦油状的产品,且只含不到1%的物质C。 |

|

Induction 归纳 |

At this point the initial model and data do not agree. The problem worries Rita and that evening she is somewhat short with her husband, Peter Minerex, but the next moming in the shower she begins to think along the following lines. Product C might frst have been formed in high yield, but it could then have been decomposed. 在这点上原始模型和数据不一致。这个问题让丽塔感到烦恼并且晚上在她的丈夫PeterMinerex面前表现得有些不高兴。但是在第二天早晨洗澡的时候,她开始沿下面的思路想:产品C可能首先已经以高产量形成,但然后它又被分解。 |

|

|

|

|

Deduction 演绎 |

A lower temperature might produce a satisfactory yield of C. Two further runs are made with the reaction temperature first reduced to 550°C and then to 500°C. 稍低些的温度可能得到C的满意产量。首先将反应温度降至550℃然后又降至500℃来做两个进一步的试验. |

|

Data 数据 |

The product obtained from both runs is less tarry and not so black. The run at 550°C yields 4% of the desired product C, and the run at 500°C yields 17%. 从这两个试验得到的产品减少了焦油状而且也不那么黑了。在温度550℃的试验中得到产品C的4%,而在温度500℃的试验中得到17%。 |

|

Induction 归纳 |

Given these data and her knowledge of the theory of such reactions, she decides she should experiment further not only with temperature but also with a number of other factors (e.g., concentration, reaction time, catalyst charge) and to study other characteristics of the product (e.g., the levels of various impurities, viscosity). 给定这些数据并根据她对该反应的理论知识,她决定应该进一步做试验,不只是考虑温度,而且考虑一些其他因子(例如,浓度、反应时间、催化剂量)并研究产品的其他特征(例如,各种纯度、黏性水平)。 |

To evaluate such complex systems economically, she will need to employ designed experiments and statistical analysis. Later in this book you will see how subsequent investigation might proceed using statistical tools.

为了经济地评价这样的复杂系统,她将要用设计的试验和统计分析。在本书的后面你会看到如何利用统计工具进行后续的研究。[2]

Exercise 1.1. Describe a real or inagined example of iterative learning from your own field — engincering, agriculture, biology, genomics, education, medicine, psychology, and so on.

练习1.1 根据自己的研究领域,如工程、农业、生物、基因学、教育、医学、心理学等,描述一个真实的或者设想的反复学习的例子.[2]

A feedback loop一个反馈回路

In Figure 1.2 the deductive-inductive iteration is shown as a process of feedback. An initial idea (hypothesis, model) is represented by M1 on the left of the diagram. By deduction you consider the expected consequences of M1 — what might happen if M1 is true and what might happen if M1 is false. You also deduce what data you will need to explore M1. The experimental plan (design) you decide on is represented here by a frame through which some aspects of the true state of nature are seen. Remember that when you run an experiment the frame is at your choice (that’s your hand holding the frame). The data produced represent some aspect (though not always a relevant one) of the true state of nature obscured to a greater or lesser extent by “noise”, that is, by experimental error. The analyzed data may be compared with the expected (deduced) consequences of M1. If they agree, your problem may be solved. If they disagree, the way they disagree can allow you to see how your initial idea M1 may need to be modified. Using the same data, you may consider altemative analyses and also possible modificalions of the original model M1′, M1”……. It may become clear that your original idea is wrong or at least needs to be considerably modifed. A new model M2 may now be postulated. This may require you to choose a new or augmented experimental design to illuminate additional and possibly different aspects of the state of nature. This could Iead to a satisfactory solution of the problen or, altemnatively, provide clues indicating how best to proceed.

在图1.2中的归纳一演绎迭代表现为一个反馈过程。一个初始的思想(假设或模型)用M表示在图的左边。通过演绎,考虑M1的期望结果——如果M1成立可能发生什么而M1不成立可能发生什么。还要推演一下需要什么样的数据来探究M1。你打算要做的试验计划(设计)在这里用一个框架来表示,通过这个框架可以看到特性的真实状态的某些方面。注意,当你进行一次试验时这个框架是在你的选择下的(即你能控制这个框架)。产生的数据表现(或多或少被“噪声”(noise)即试验误差弄模糊的)特性真实状态的某个方面(虽然不总是相关的)。分析的数据可以与M1的期望(推演)结果进行比较。如果一致,你的问题可能得到解决。如果不一致,那么它们不一致的情况可能启示你去发现你的原始想法M1的问题及需要如何去修改。利用同样的数据,可以考虑另外的分析以及原始模型可能的修改M1’,M2” ……可以弄清楚你的原始思想是否是错的或者至少要做相当地修改。这可能要求选择一个新的或者扩充的试验设计去阐明该特性的状态的可能不同的方面。这可会使该问题得到一个满意的解决,或者提供一些线索提示下一步最好如何去进行。[2]

如果本文对你有所启发,欢迎点赞👍、推荐❤️、分享📣

一起学习,一起实践!「学到了,再整理分享,所以学到最多的永远是作者…」

顺祝大家国庆节快乐!